Reetika Choudhury

Alexander’s invasion of India is often seen as a great Western victory over the disorganized East. However, it is believed that Alexander’s army suffered a fate worse than Napoleon’s disastrous campaign in Russia. In 326 BCE, Alexander led a formidable force of over 41,000 soldiers into India. This diverse army included Macedonian soldiers, Greek cavalry, Balkan fighters and Persian allies.

The most memorable battle of this campaign was the Battle of Hydaspes (Jhelum), where Alexander’s forces faced King Porus of the Paurava kingdom in western Punjab. For centuries, it was believed that Alexander’s army triumphed due to their superior courage and strength, as recorded by Greek and Roman historians.

Later, British historians perpetuated this legend, depicting the campaign as a triumph of the organized West over the chaotic East. Despite Alexander only defeating a few minor kingdoms in northwestern India, some colonial writers claimed his conquest of India was complete. In reality, much of India was unknown to the Greeks, so claiming Alexander conquered India is like saying Hitler conquered Russia just because the Germans reached Stalingrad.

Alexander’s Struggles in the Indian Valleys

Alexander faced immediate trouble as soon as he crossed into India. In the valleys of Kunar, Swat, Buner and Peshawar, he encountered strong resistance from the Aspasioi and Assakenoi tribes, also known in Hindu texts as the Ashvayana and Ashvakayana. Despite their smaller size compared to Indian standards, these tribes did not easily succumb to Alexander’s forces. The Assakenoi, in particular, put up a fierce fight from their mountain strongholds of Massaga, Bazira, and Ora.

The battle at Massaga was especially brutal and gave Alexander a taste of what awaited him in India. On the first day, after intense fighting, Alexander’s forces had to retreat with significant losses, and Alexander himself was seriously wounded in the ankle. After four days of fighting, the king of Massaga was killed, but the city still refused to surrender. Leadership then passed to his elderly mother, who rallied all the women to join the fight.

Realizing his campaign was at risk, Alexander called for a truce, which the Assakenoi accepted. The old queen, trusting Alexander, let her guard down. That night, while the citizens of Massaga celebrated and slept, Alexander’s troops attacked and massacred everyone in the city. A similar slaughter occurred in Ora. However, the fierce resistance from the Indian defenders had significantly weakened Alexander’s army and shaken their confidence.

The Fiercest Battle and The Clash with King Porus at Hydaspes

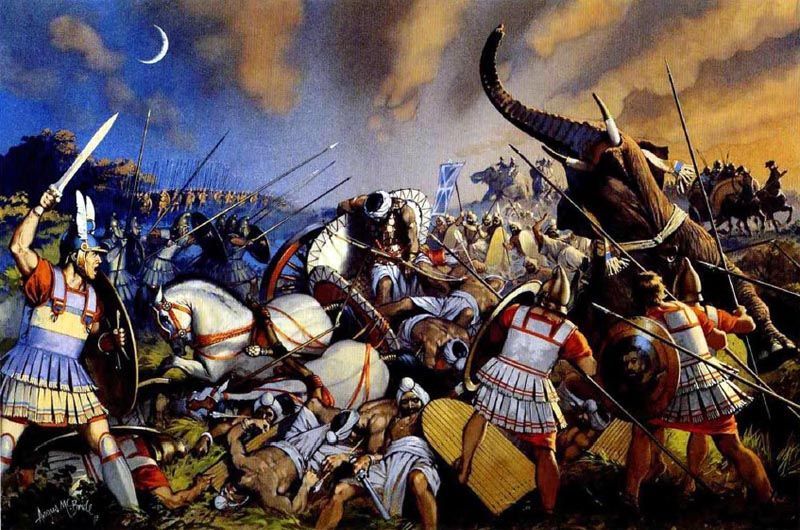

Throughout his conquering career, Alexander the Great faced his toughest battle at the Battle of Hydaspes in 326 BCE. Here, he encountered King Porus of Paurava, a small but wealthy Indian kingdom on the river Jhelum. According to Greek accounts, Porus was an impressive figure, standing seven feet tall. In May 326 BCE, the European and Paurava armies prepared for battle across the Jhelum River. It was a sight to behold as Alexander’s 34,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry, reinforced by the Indian king Ambhi of Taxila, faced Porus’s 20,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry, and 200 war elephants. Ambhi had allied with Alexander, hoping to gain Porus’s kingdom.

Paurava, being a relatively small kingdom, likely couldn’t maintain such a large standing army, so many of its soldiers were probably hastily armed civilians. The Greeks often exaggerated enemy numbers. For days, the armies watched each other from opposite sides of the river. Alexander’s army, having already lost many soldiers in previous battles against Indian mountain cities, were nervous about facing Porus’s formidable army. They had heard stories of the destruction caused by Indian war elephants, which, like modern battle tanks, terrified the Greek cavalry’s horses.

Another powerful weapon in the Indian arsenal was the two-meter bow, capable of launching large arrows that could pierce multiple soldiers. When the battle began, it was fiercely contested. The Indian longbows sent volleys of heavy arrows into the Greek formations, and the first wave of war elephants charged into the Macedonian phalanx, armed with 17-foot-long sarissas. Some elephants were impaled, but a second wave followed, trampling soldiers and lifting others with their trunks for Indian soldiers to kill. The Macedonians, in fear, fell back, allowing the Indian infantry to press the attack.

In an early charge, Porus’s brother Amar killed Alexander’s beloved horse, Bucephalus, forcing Alexander to dismount. This was significant, as Alexander’s elite bodyguards had never let an enemy harm him or his mount before. In this battle, Indian troops not only broke through Alexander’s protective circle but also killed one of his top commanders, Nicaea.

Roman historian Marcus Justinus wrote that Porus challenged Alexander, who charged on horseback. In their duel, Alexander was unseated and at the mercy of Porus’s spear, but Porus hesitated, giving Alexander’s bodyguards time to save him.

Greek historian Plutarch noted that Indian morale remained high. Despite initial setbacks, such as their chariots getting stuck in the mud, Porus’s army rallied and fought back with exceptional bravery.

Now according to Greek sources, Alexander won the war and treated Porus with respect and let him go despite winning the battle. Considering Alexander’s past actions, and the fact that his horse was killed by Porus, this seems quite inconsistent. Even if we accept that Alexander had won the war, would someone who is set out to conquer the world let a ruler go and return his kingdom, after suffering such huge losses from him?

Alexander’s Withdrawal from the East

Although it is said that the Greeks claimed victory, the fierce resistance from Indian soldiers and ordinary people left Alexander’s army deeply shaken. They refused to go any further east, no matter what Alexander said or did. His troops were on the verge of mutiny. According to Plutarch, the Greek historian, the tough battle with King Porus took a toll on their morale. They had a hard time defeating an army of just 20,000-foot soldiers and 2,000 horsemen, so they were strongly against Alexander’s plan to cross the Ganges River. Beyond the Ganges, they were told, lay a land with even more skilled soldiers, bigger elephants, and braver kings and soldiers.

On the other side of the Ganges was the powerful kingdom of Magadh, ruled by the Nandas, who had one of the largest and most powerful armies in the world. Plutarch notes that the Macedonians lost their courage when they learned the Nandas had 200,000 infantry, 80,000 cavalry, 8,000 war chariots, and 6,000 fighting elephants. Alexander’s army would have faced certain defeat.

Far from the Indian heartland, Alexander finally ordered a retreat, much to the great relief and joy of his soldiers.

According to Military History magazine, although there were more battles afterward, Alexander’s injury marked the end of his personal military campaigns. The damage to his lung never fully healed, leaving him in constant pain with every breath. Alexander never recovered from his injury and eventually died in Babylon.

Reassessing Alexander’s Disgraceful Retreat from India

Interestingly, Indian historical texts make no mention of Porus, raising questions about his significance as a ruler. This absence could imply that Porus was a relatively minor local king rather than a prominent figure in the broader Indian polity. If Porus was indeed a minor chieftain, Alexander’s struggle against his forces might suggest that his campaigns against more formidable Indian empires would be even more devastating.

The vast and diverse Indian subcontinent during Alexander’s time was home to several powerful kingdoms and empires. The Nanda Empire was a major power in northern India, possessing vast armies and resources. If Alexander faced significant difficulties against a minor ruler like Porus, whose name is not even mentioned in any Indian texts, it suggests that his army might have encountered even greater challenges had they engaged with larger Indian states.

Our history books tell us that Alexander claimed victory in India by winning over Porus, and he gave back his kingdom out of honor, but like we discussed, this seems to be totally illogical and inconsistent. The truth is that Alexander was on a mission to conquer the world and his army was crushed in India, which forced him to retreat. This might seem like a small issue, but it might give young minds the impression that India rulers were weak, and it was only out of “Alexander’s mercy” that our nation was spared from his rule.